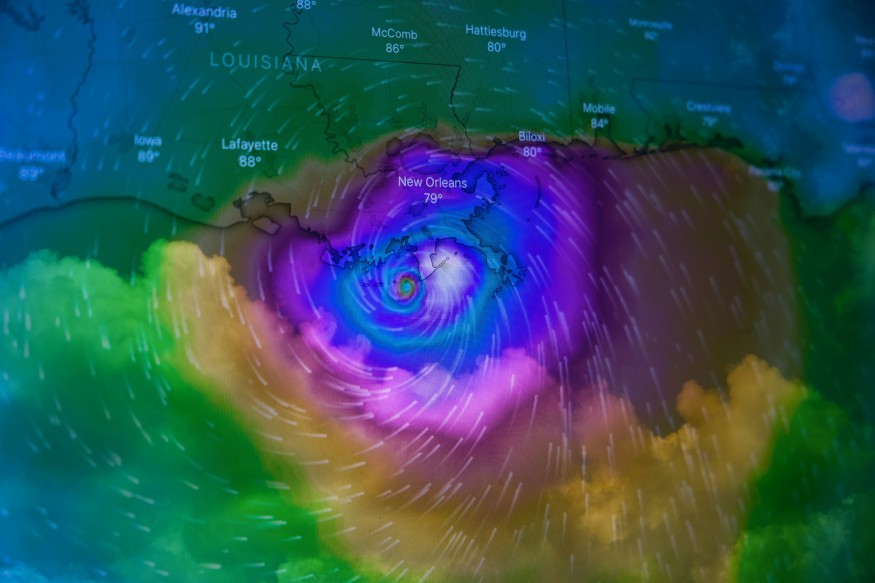

Rising ocean temperatures are reshaping how typhoons and hurricanes form and intensify. Typhoon intensity now scales directly with the heat content of tropical oceans, with warmer surface waters boosting maximum wind speeds by 10–20 mph. Recent Atlantic hurricanes, including Ian and Lee, reached Category 5 intensity largely due to human-induced warming, highlighting the link between ocean heat and storm power. Rapid intensification events, in which winds surge over 30 knots within 24 hours, are occurring 25–50% more frequently, creating storms that strengthen far faster than historical patterns suggest.

Extreme storms are also lingering longer, dropping far more rainfall over impacted regions. Weakened steering currents leave hurricanes stalled, generating localized deluges that can triple previous rainfall records. Hurricanes like Harvey demonstrate how stalled storms can unleash 60 inches of rain in just a few days. Combined with ocean heat expansion, these factors make modern typhoons and hurricanes both stronger and more destructive than ever, with storm surge, rainfall, and wind intensity all climbing above historical baselines.

Typhoon Intensity Driven by Ocean Heat Content

Typhoon intensity depends on the heat stored in tropical ocean layers, which acts as fuel for storm energy. Rising sea surface temperatures and expanding warm pools allow storms to generate stronger winds and sustain peak intensity longer. Climate change has amplified these factors, making modern typhoons more powerful and destructive than historical storms.

- Typhoon intensity is fueled by tropical cyclone heat potential, stored in the upper ocean layers.

- A single square mile of the upper 50 meters can hold energy equivalent to hundreds of Hiroshima bombs.

- Climate change has increased the occurrence of these hotspots 400–800 times in regions like the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

- Sea surface temperature anomalies of 1–2°C supercharge evaporation, producing strong updrafts that efficiently convert heat into wind energy.

- Hurricanes like Lorenzo, Ian, and Lee reached Category 5 intensity solely because of these human-driven ocean temperature increases.

- Deep warm pools are now 60–70% larger than in the 1980s, allowing storms to maintain strength after landfall.

- Reduced vertical wind shear supports taller, stable eyewalls that channel shear stress into rotational torque.

- Subsurface heat reservoirs now play a crucial role, sustaining storms and amplifying potential coastal damage.

Hurricane Science Rapid Intensification Mechanisms

Rapid intensification events make hurricanes increasingly dangerous, as storms can strengthen dramatically in very short periods. Warmer oceans and higher atmospheric moisture levels are driving these surges, while stalled storms increase rainfall hazards. Understanding the mechanisms behind rapid intensification is critical for predicting extreme storm impacts.

- Rapid intensification can increase winds by over 30 knots within 24 hours.

- The probability of such events has risen by 25–50% due to warmer oceans and by 7% per 1°C of warming, with more moisture.

- Storms like Milton, which experienced a 120 mph wind jump, show the effect of extreme Gulf heat anomalies on peak intensities.

- Weakened steering currents prolong storm duration, increasing rainfall by up to 50% over impacted areas.

- Warmer mid-troposphere layers reduce atmospheric stability, allowing updrafts to reach 15 km and generate stronger outflows.

- Climate models suggest overall hurricane frequency may remain stable, but the proportion of Category 4–5 storms will double by the century's end.

- Extreme storms can now drop three times as much precipitation as historical baselines, creating unprecedented coastal and inland risks.

Extreme Storms: Surge, Ocean Heat, and Future Risks

Storm surges are rising as stronger winds and rising sea levels add 15–30 cm to coastal flooding. Katrina's 2005 floods were about 15% higher than they would have been without thermal expansion, and stalled storms like Helene and Milton can dump 20–50% more rain than historical events. Reduced wind shear lets storms maintain peak intensity longer, so they weaken more slowly after landfall.

Deep ocean heat reservoirs store 90% of excess climate energy, feeding storms even when surface waters cool. Human-driven warming accounts for most of this expansion, slowing storm movement and increasing rainfall footprints by up to 50%. These heat pools create the conditions for longer-lasting surges and stronger Category 5 events.

Models predict the share of Category 4–5 storms will double by 2100 under moderate warming, with rainfall rising 10–20% globally. Studies show about 80% of recent major storms carry clear climate fingerprints, linking ocean heating to stronger, slower, and deadlier typhoons. Tools like the CSI:Ocean index quantify human influence, helping forecast future hurricane risks.

Stronger Storms Ahead: Understanding the Climate Link

Typhoons and hurricanes are growing more intense, fueled by warmer oceans and subsurface heat reservoirs. Storms now reach higher wind speeds, stall longer over land, and dump far more rainfall than their historical counterparts.

Rapid intensification events and extended surges make preparation critical, while climate models suggest that Category 4–5 storms will become the norm rather than the exception. As ocean temperatures continue to rise, understanding the science behind storm strength is essential for forecasting, mitigation, and safeguarding coastal communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why is typhoon intensity increasing with climate change?

Warmer ocean temperatures increase evaporation, fueling stronger winds and convection. Even a 1–2°C rise boosts maximum wind speeds by 10–20 mph. Increased heat content also raises the likelihood of rapid intensification events. This creates storms that are both stronger and faster to develop.

2. Are extreme hurricanes happening more often?

The overall number of hurricanes may remain stable or slightly decline, but the proportion of Category 4–5 storms is rising. Stronger storms are more frequent due to higher ocean heat content. Weakened steering currents prolong storms, amplifying rainfall and surge. This makes extreme events deadlier, even if total storm counts remain similar.

3. How does sea level rise affect storm surges?

Global sea level rise adds 15–30 cm to coastal flood heights. Thermal expansion intensifies surge impacts on top of wind-driven waves. Coastal storms like Katrina saw surges 15% higher than pre-industrial baselines. Rising seas compound the damage from already stronger storms.

4. What is the role of subsurface ocean heat in hurricane strength?

Deep ocean heat stores excess climate energy that can sustain storm intensity. These reservoirs fuel updrafts even if surface temperatures drop slightly. Human-driven warming has expanded these zones 60–70% since the 1980s. They prolong storm strength and enhance rainfall and surge impacts.

Originally published on Science Times

© 2026 ScienceTimes.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission. The window to the world of Science Times.