As the Sahel's vegetation grows, new climate models reveal that it might exacerbate the West African monsoon.

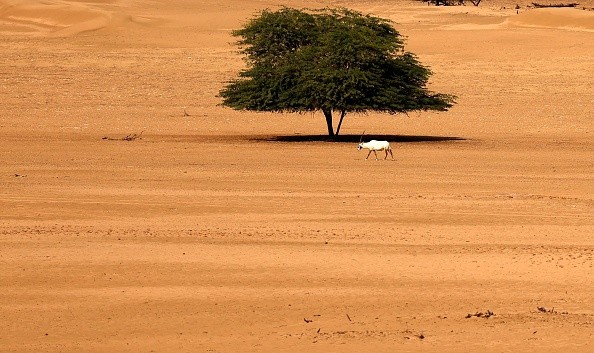

Africa's "Great Green Wall" initiative is a suggested line of trees of about 8,000-kilometer whose role is to prevent the Sahara from extending southward.

Observations from the past and future imply that this greening might have a significant impact on the climate of northern Africa and even beyond.

Green Sahara Linked to Changes in Monsoon's Intensity and Location

An ambitious initiative is underway to plant 100 million hectares of trees in the semiarid zone that stretches from the desert's southern border to the Sahel region, according to Science News.

According to models presented on December 14 at the American Geophysical Union's autumn conference, the finished tree line could quadruple rainfall in the Sahel and lower average summer temperatures over most of northern Africa and into the Mediterranean.

However, according to the findings of the research, the hottest sections of the desert would become even hotter.

According to previous research, a "green Sahara" has been related to changes in the strength and position of the West African monsoon. Over northern Africa, the primary wind system delivers dry, warm air to the south in the colder months while bringing a little more rain to the north in summer.

For example, a green Sahara phase that occurred from 11,000 to 5,000 years ago was caused by fluctuations in the monsoon's strength and its northward or southerly extension.

It was during the 1930s when Hungarian explorer László Almásy, who served as the inspiration for actor Hugh Grant's character in the 1996 film The English Patient, uncovered Neolithic cave and rock art in the Libyan Desert depicting humans swimming.

How Changes in Plant Cover Intensify Monsoon Shifts

Earth's orbital cycles affect the amount of incoming solar radiation that warms the West African area, which has influenced past shifts in the monsoon.

Francesco Pausata, a climate dynamicist at the Université du Québec à Montréal who performed the new simulations, thinks that orbital cycles don't convey the complete picture. As he points out, scientists are now aware that changes in plant cover and general dustiness may significantly increase such monsoon swings.

Deepak Chandan, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, argues that more vegetation helps produce a local pool of moisture by boosting the amount of water cycling from soil to atmosphere.

According to Chandan, vegetation also results in a darker land surface than the white sands of the desert, which allows the ground to absorb more heat.

As a bonus, vegetation helps to reduce the amount of dust in the air. In order to increase the amount of solar radiation reaching the land, fewer dust particles are needed. As a result, the land is hotter and more humid than the ocean, resulting in a greater disparity in air pressure. So the monsoon winds will be more powerful and intense.

Africa's Great Green Wall Project

Africa's Great Green Wall was conceived in the 1970s and 1980s, when the once-fertile Sahel region began to dry up due to a combination of climate change and human activity. A long-standing strategy is to build a protective wall of vegetation around an expanding desert.

As the Dust Bowl spread across the Midwest and Texas in the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enlisted the help of the U.S. Forest Service and the Works Progress Administration to plant massive groves of trees.

Great Green Wall of Africa, a project spearheaded by the African Union, began in 2007 and is presently around 15 percent complete. Supporters anticipate the finished tree line would not only halt the expansion of the desert, but will also enhance food security and provide millions of jobs in Senegal and Djibouti.

Pausata adds further research is needed to determine the long-term impact of the completed greening on local, regional, and global climate. He claims that the project is fundamentally a geoengineering one, and that anybody considering this or any other kind of geoengineering should thoroughly research the potential consequences.

Related Article : Africa's Great Green Wall: Only 4% Complete on 2030 Deadline

For more news, updates about climate change and similar topics don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2026 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.