Mass die-off of birds on Mexico coast is due to El Niño.

Bird flu was ruled out when an autopsy revealed that the large die-off of birds on Mexico's coast was caused by El Niño.

The government, however, stated on Thursday that the enormous die-off was caused by rising Pacific Ocean currents connected with El Niño, not bird flu.

According to Mexico's Agriculture Department, testing on the deceased birds found that they died of famine rather than avian bird flu.

El Niño Warms Surface Water and Starves Birds

According to the agency, heated surface water in the Pacific caused by El Niño can drive fish into deeper, colder water, making it more difficult for birds to obtain food.

Sooty Shearwaters, seagulls, and pelicans made up the majority of the deceased birds. They died in states that extended from Chiapas, on the borders of Guatemala, through Baja California, to the north and west.

According to the government, examinations performed by veterinarians and expert biologists revealed that the animals died of malnutrition. The most likely explanation of this epidemic occurrence is the warming of the Pacific seas caused by the El Nio weather impact, which encourages fish to move farther down to colder waters, limiting sea birds from finding food, Phys Org reports.

El Niño This Year

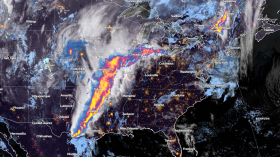

El Niño is a naturally occurring phenomenon that causes transient and irregular warming of the Pacific Ocean. It causes changes in worldwide weather patterns.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NOAA climate scientist Michelle L'Heureux told AP News that El Niño formed this year a month or two earlier than usual, which "gives it room to grow," and that there is a 56% chance it will be considered strong, with a 25% chance it will reach supersized levels.

Typically, an El Niño reduces hurricane activity in the Atlantic, providing respite to coastal communities from Texas to New England, Central America, and the Caribbean that have been battered by recent record-breaking storms. Due to unprecedentedly high temperatures in the Atlantic, forecasters do not anticipate the occurrence of El Niño winds that typically weaken numerous storms, thus offsetting the possibility of it happening this time.

Hurricanes build and expand as they pass over warm salt water, and the tropical Atlantic Ocean is "exceptionally warm," according to Kristopher Karnauskas, University of Colorado associate professor. As a result, NOAA and others forecast a near-average Atlantic hurricane season this year, AP News reported.

Also Read: Avian Flu Kills 21 Critically Endangered Condors in 25 Days - Arizona

Effect on Animals

El Niño would have a wide range of effects on both terrestrial and marine ecosystems, including droughts, fires, coral bleaching, increased precipitation, invasions of predatory marine species such as crown-of-thorns starfish, disturbances to marine food chains, and kelp forest die-offs.

Scientists recall a particularly awful period for coral reefs between 2014 and 2017. High temperatures caused by an El Niño climatic pattern affected around three-quarters of the world's reefs in both hemispheres, pushing corals to expel their life-sustaining zooxanthellae and leaving them ghostly white, which is known as bleaching. As a result of the bleaching, around 30% of the world's corals died. Others are still recovering.

And now, at a time when the world's temperatures are higher than they have ever been since the beginning of the modern period owing to human-caused climate change, scientists believe that another El Niño will form later this year. If they are correct, this El Niño could cause significant damage to both terrestrial and marine ecosystems, including the world's coral reefs, which are already having trouble keeping up with environmental stressors such as pollution, overfishing, and warming water, Monagbay reports.

Related Article: Global Chocolate Consumption Linked to 1.5 Million Hectares of Deforestation in Africa

© 2024 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

![Tsunami Hazard Zones: New US Map Shows Places at Risk of Flooding and Tsunamis Amid Rising Sea Levels [NOAA]](https://1471793142.rsc.cdn77.org/data/thumbs/full/70325/280/157/50/40/tsunami-hazard-zones-new-us-map-shows-places-at-risk-of-flooding-and-tsunamis-amid-rising-sea-levels-noaa.jpg)