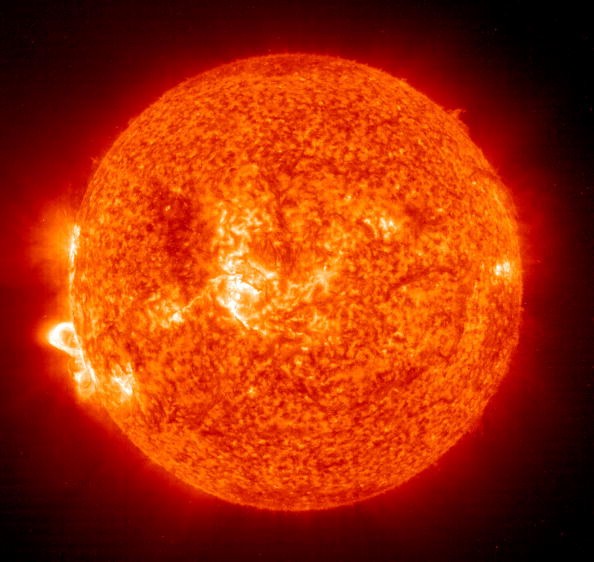

Since its launch in February 2020, the Solar Orbiter project will conduct its closest flyby of the sun on Saturday.

The spacecraft will approach the sun at 31 million miles (50 million kilometers), less than one-third of the distance between the star and Earth. Solar Orbiter will be able to pass through the orbit of Mercury, the nearest planet to the sun.

Because it will take time to download and evaluate everything obtained during the flyby, the European Space Agency, which oversees the program alongside NASA, will provide the first photographs and data within a few weeks.

Solar Orbiter

Solar Orbiter's progress may be tracked using a program provided by the European Space Agency to follow the sun explorer's route.

The Solar Orbiter's ten sensors will all be operational simultaneously, ready to monitor the solar wind and keep a watch out for small flares known as campfires, which were first detected in the mission's initial photographs in 2020. High-resolution telescopes are also carried by spaceship.

The information gathered during the flyby might aid scientists in solving some of the most vexing solar mysteries, such as why and how the sun's temperature rises through its atmosphere.

Solar Orbiter will also take high-resolution photos of the sun and record the solar wind, a kinetic flow of charged particles that flows away from the sun.

"As far as Solar Orbiter observations of the Sun are concerned, we are now 'entering the unknown,'" stated Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter project scientist, in a statement.

Solar Orbiter's most recent photographs provide a fresh viewpoint on the sun that catches unparalleled detail, including the highest-resolution image of the sun's outer atmosphere ever taken. On March 7, the photographs were captured when the spacecraft passed directly between Earth and the sun.

Distance

At around 46 million miles (74 million kilometers) from the sun, the spaceship was midway between the two celestial bodies.

One of the images, acquired with the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument, is the first full-sun image in 50 years to be shown in ultraviolet light.

Using Various Wavelength

Researchers can use different wavelengths of light to investigate temperature variations between the sun's solar surface and the corona or outer atmosphere.

The corona may reach a temperature of a million degrees Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), whereas the surface temperature is 5,000 degrees Celsius (9,000 degrees Fahrenheit). The Solar Orbiter might reveal why the temperature appears to climb rather than fall as one moves farther from the sun's core.

This is only one of Solar Orbiter's initial near encounters of the sun; several more flybys are planned in the following years to get it much closer to the star. The spacecraft will gradually increase its attitude to explore the sun's hitherto unseen polar regions.

Solar Orbiter has a multilayer heatshield, a unique burned bone covering dubbed "Solar Black," sliding doors to protect its instruments and solar arrays that can tilt away from the worst heat and cooling components within the spacecraft. These components work together to protect the spacecraft from melting as it examines the sun.

The sun is becoming more active, and Solar Orbiter has kept track of its outbursts.

On March 2, the sun ejected a massive solar flare. The outburst was classified as M-class, the fourth most powerful of the five types of solar flares. According to NASA, a burst of this power might result in temporary radio blackouts at Earth's poles and small radiation storms that could harm astronauts on the International Space Station.

The Solar Orbiter's Extreme Ultraviolet Imager acquired a video of the stunning incident.

Meanwhile, on February 15, the Parker Solar Probe, which became the first spacecraft to "touch the sun" at the end of 2021, was exposed to the extremes of a massive solar prominence when the sun spewed tons of charged particles in Parker's direction.

Suppose solar flares and storms seem to be happening more frequently. In that case, the sun is ramping up activity as it approaches solar maximum, as shown in the stunning flare on February 15 (also taken by Solar Orbiter) and the solar storm that disrupted SpaceX's Starlink satellites in February.

Space weather created by the sun, such as solar flares and coronal mass ejection events, may influence the electrical grid, satellites, GPS, airplanes, rockets, and humans in space; therefore, understanding the solar cycle is critical.

The sun completes a solar cycle of calm and stormy activity every 11 years and begins a new one. The current solar cycle, Solar Cycle 25, started in December 2019, and the next solar maximum, when the sun is at its most active, is expected in July 2025.

Changes in Solar Activities

The sun changes from a quiet to a solid and active phase during a solar cycle. The number of sunspots visible over time is used to track this activity. The explosive flares and ejection events that unleash light, solar material, and energy into space originate in sunspots or dark patches on the sun.

As we approach solar maximum, Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe will be in a prime position to observe.

Related Article : Expert Warns 'Situation Worse than Covid' if Government Ignores Solar Flare Defense

For more cosmic news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2026 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.