Aircraft can become more environmentally friendly, new research suggests, by choosing flight paths that reduce the formation of their distinctive condensation trails.

Described in the journal Environmental Research Letters, researchers from the University of Reading have shown that aircraft contribute less to global warming by avoiding the places where the thinly shaped clouds, called contrails, are produced - even if that means flying further and emitting more carbon dioxide.

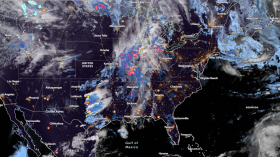

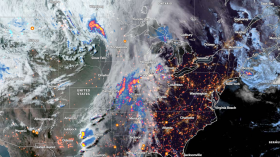

Contrails only form in parts of the sky where the air is very cold and moist, which is often in the ascending air around high pressure systems. Sometimes they remain in the air for hours, appearing like normal wispy clouds, trapping some of the infrared energy that radiates from Earth into space, therefore having a warming effect.

Previous research shows that on average, seven percent of the total distance flown by aircraft is in the type of air that contrails form in.

And though aviation emissions accounted for six percent of UK total greenhouse gas emissions in 2011, this study shows that scientists must consider more than just carbon dioxide (CO2) when discussing ways to make air travel more eco-friendly.

Recent research has shown that the amount of global warming caused by contrails could be as large, or even larger, that the contribution from aviation CO2 emissions.

"If we can predict the regions where contrails will form, it may be possible to mitigate their effect by routing aircraft to avoid them," lead author Dr. Emma Irvine said in a press release.

"Our work shows that for a rounded assessment of the environmental impact of aviation, more needs to be considered than just the carbon emissions of aircraft."

This research doesn't mean that planes can fly to their heart's content all over the sky; there is a limit. For larger aircraft, which emit more CO2 than smaller ones, flying further to avoid contrails makes sense ecologically, but only if the re-route adds less than 60 miles to the trip.

"We believe it is important for scientists to assess the overall impact of aviation and the robustness of any proposed mitigation measures in order to inform policy decisions," Irvine added. "Our work is one step along this road."

© 2024 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.