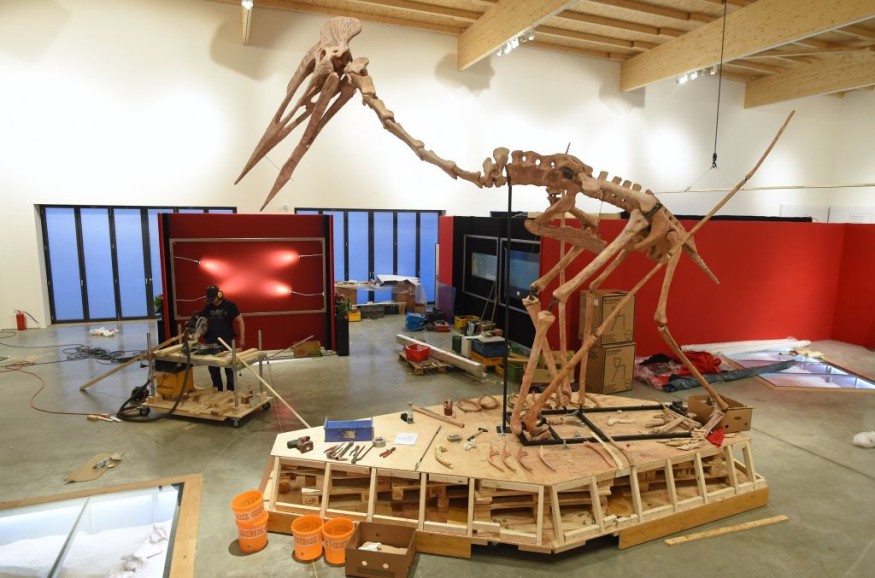

Scientists created a functioning replica of an early flying dinosaur to test a theory about how the appendages evolved.

Dinosaur Robot and Grasshopper

Many dinosaur species developed wings long before they flew.

Scientists believe that these early structures may have assisted the animals in anything from attracting mates to protecting hatchlings. However, a robot dinosaur produced by South Korean researchers implies a quite different function.

The scientists created the robot to test their theories concerning the origins of bird wings and tails.

Dinosaur experts have proposed a variety of benefits for little "proto-wings." They could have served as insect nets, preventing prey from escaping, allowing for lengthy hops and gliding, and warming the animal and its newborn progeny.

An additional theory is that dinosaurs utilized their feathery appendages in intimidating displays to flush insects and other prey from their hiding spots. The South Korean team's "flush and pursue" method is still used successfully in the northern mockingbird and bigger roadrunner.

To test their theory, the scientists placed Robopteryx, a peacock-sized machine with paper wings based on Caudipteryx, a winged, flightless dinosaur, in front of unsuspecting grasshoppers and had it execute various wing and tail movements.

These were created to imitate demonstrations that Caudipteryx may have conducted approximately 124 million years ago in the early Cretaceous.

The researchers report how grasshoppers were more likely to flee when Robopteryx used its wings than when it didn't. In the most successful demonstrations, the robot swept them back before swooping down and forward.

The insects fled more frequently when the researchers added white patches to the black wings, and Robopteryx added huge tail feathers to the show, according to the authors.

Some grasshoppers hopped away as Robopteryx approached, but many would freeze or hide beneath a plant stem, shifting their position in preparation for escape.

"In that situation, they are quite well camouflaged and not as easy to spot as during a sudden jump," said Prof Piotr Jablonski, a behavioral ecologist on the team at Seoul National University.

Flush Display

The researchers believe that flush displays activate ancient escape circuitry that is built into the insect's brain. The defense mechanism sends the grasshopper running, but once out in the open, it is more likely to become the predator's food.

If some feathered dinosaurs hunted in this manner, the behavior could have influenced the evolution of larger and stiffer feathers, they argue.

Other scientists, however, may require some convincing. Jablonski stated that the researchers received "multiple refusals" from 11 publications before the study was assessed and accepted for Scientific Reports.

Michael Benton, a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Bristol stressed that they are correct that flight-like feathers evolved in dinosaurs when they only had little wings that were too small for powered flight.

"However, these pennaceous feathers are very much adapted to make an unbroken wing surface, and the first feathered dinosaurs may have used them in gliding from spot to spot," he added.

People frequently remark 'half a wing is no use', although many current gliding lizards and mammals have half a wing, which is a great adaption for non-powered flying or gliding.

Related Article : Meet Spinosaurus: The First Swimming Dinosaur

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.