The effectiveness of two common heat-reducing technologies used in the urban US have been assessed in a new study, which reveals that unaccounted for effects in some regions of the country may render the systems less effective than previously believed.

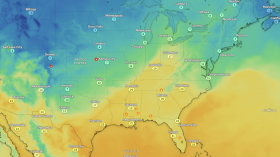

As urban populations in the US continue to grow, the expansion of roads and buildings will contribute to a measurable surface temperature increase of as much as 3 degrees Celsius, according to the research by the University of Arizona and the Environmental Protection Agency.

This temperature increase will come alongside any additional increased temperature as a result of increasing greenhouse gases, the researchers said.

However, there are strategies that can impact the urban-life-induced surface temperature increases, but they will not have a blanket effect across the nation, the researchers said.

By installing white colored roofing on buildings or by designing green gardens on rooftops, some - but not all - of this temperature increase can be mitigated, the researchers report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research explored the effectiveness of the most common adaptive technologies used to reduce warming as a result of urban expansion, finding that these technologies do work, but they work better in some areas than others.

"This is the first time all of these approaches have been examined across various climates and geographies," said Matei Georgescu, an assistant professor in Arizona State University's School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning . "We looked at each adaptation strategy and their impacts across all seasons, and we quantified consequences that extend to hydrology (rainfall), climate and energy. We found geography matters."

For instance, the white roofs used to lower temperatures in the California Central Valley do not provide the same benefits in other parts of the country, such as Florida, the researchers found.

"Assessing consequences that extend beyond near surface temperatures, such as rainfall and energy demand, reveals important tradeoffs that are oftentimes unaccounted for," the researchers said in a statement.

Cool roof systems, for example are very effective in summertime at lowering temperatures inside a building, but during winter in the northern regions of the US, these same roof systems continue to produce a cooling effect that requires the building's occupants to use more heating they they would normally need to, which takes a toll on the net energy savings of the system.

"The energy savings gained during the summer season, for some regions, is nearly entirely lost during the winter season," Georgescu said.

But in other regions of the country, such as Florida, the cool roofs have entirely different effects.

"In Florida, our simulations indicate a significant reduction in precipitation," he said. "The deployment of cool roofs results in a 2 to 4 millimeter per day reduction in rainfall, a considerable amount (nearly 50 percent) that will have implications for water availability, reduced stream flow and negative consequences for ecosystems. For Florida, cool roofs may not be the optimal way to battle the urban heat island because of these unintended consequences."

Georgescu added that, while additional research is needed, the current results can be used to aid urban planners in choosing the most effective heat-reduction technology for their region, rather than relying on a blanket approach.

Click through to watch Georgescu go into more detail about his research in a video from ASU.

© 2024 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.