Coral reefs sometimes require more than a decade to recover from a climatic disaster. A new study has found that some coral species can take almost 13 years to get back to their original state.

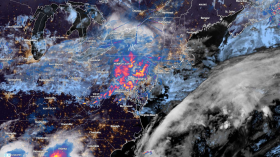

The El Niño event of 1997-98 is the first such extensively recorded event in the world. The change in weather pattern left many areas flooded, while other regions of the world experienced drought. The event first began in the spring of 1997 off the coast of Peru. About 2,100 people were killed and led to property damages worth 33 billion [U.S.] dollars.

The event also caused severe coral bleaching. "Coral reefs are perhaps the most diverse marine ecosystem on Earth, potentially holding 25% of the known marine species. Yet they are under intense threat from a range of local human activities and, in particular, climate change. Any impact on the corals is going to have major knock on effects on the organisms that live on coral reefs, such as the fish, and if climatic events become more frequent, as is suggested, it is likely corals will never be able to fully recover," said Professor Martin Attrill, Director of Plymouth University's Marine Institute and one of the study authors.

The study was conducted by researchers from Plymouth University and the Universidad Federal da Bahia in Brazil, who looked at the effects of catastrophic El Niño event of 1997-98 on eight species of scleractinian corals. The data for the study came from Brazilian Meteorological Office. Researchers analyzed the environmental conditions before and after the event.

Researchers found that there was a significant increase in sea water temperatures in 1998. Most of the coral species were destroyed and few disappeared from the reef for about seven years.

The density of the reefs was also greatly reduced post the El Niño event of 1997-98. However, current research shows that the density of the reefs is now similar to the one before the event.

"El Niño events give us an indication of how changing climate affects ecosystems as major changes in the weather patterns within the Pacific impact the whole world. If the reefs can recover quickly, it is probable they can adapt and survive the likely changes in water temperature ahead of us," Attrill added.

The study is published in the journal PLOS-ONE.

© 2024 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.