A large-scale volcanic eruption in Iceland provided scientists with the answers they needed to resolve a long-standing debate regarding how sulfur emissions brighten clouds. In a recent study, researchers from the University of Washington were able to show how sulfur emissions brighten clouds by creating smaller water droplets that are more reflective.

"This eruption is a chance to nail down one of the big uncertainties in climate models," Daniel McCoy, first author of the recent study and a UW doctoral student in atmospheric sciences, said in a news release. "You can see the effect over an entire ocean for a two-month period. It was a pretty unique geophysical event within the satellite record."

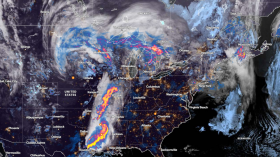

Until now, scientists have had trouble measuring how clouds are impacted by sulfur emissions, despite the vast quantities that have been pumped into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution. The Bardarbunga volcano, however, recently seeped lava and sulfur gases for a six-month-long period lasting from the summer of 2014 through early 2015. During this time, researchers took advantage of the huge eruptions that filled Iceland's skies with ash and monitored data collected by NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) - an instrument that measures the size of droplets in the marine cloud layer.

So what did they find? The MODIS revealed the droplets were the smallest in a 14-year record of observations. This confirms that particles emitted into the atmosphere not only cool the planet by blocking or reflecting light, but that low-level sulfur emissions also influence the formation of clouds.

"The effect of volcanic emissions on clouds has been a difficult one to quantify because of the ephemeral nature of most events," Dennis Hartmann, co-author and a UW professor of atmospheric sciences, said in a statement. "This eruption provides a natural laboratory that lets us test how clouds respond to aerosols."

Aerosols are minute particles suspended in the atmosphere that are relatively large and scatter or absorb sunlight. However, when sulfate aerosols are present, they cause the number of cloud droplets to increase but make the droplet sizes smaller, reflecting more sunlight.

"One of the big uncertainties regarding climate change is how much human-produced aerosols have offset the warming until now," Hartmann continued. "We hope the data from this eruption will improve the model simulations of cloud effects, and narrow the uncertainties in projections of the future."

Essentially, when clouds are more reflective, or brighter, the planet is shielded from the simultaneous effects of rising carbon dioxide emissions. Therefore, humans' impact on cloud formation has remained one of the biggest uncertainties concerning climate models.

"The same way that the Mount Pinatubo eruption in 1991 was a big on-off signal that allowed us to evaluate models' response to volcanic forcings, I think this Iceland eruption is a unique event that will help us to better understand the interaction between aerosols and clouds," McCoy concluded.

Their findings were recently published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

For more great nature science stories and general news, please visit our sister site, Headlines and Global News (HNGN).

-Follow Samantha on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13

© 2024 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

![Climate Change is Reducing Dust Levels Worldwide as Arctic Temperature Warms [Study]](https://1471793142.rsc.cdn77.org/data/thumbs/full/70320/280/157/50/40/climate-change-is-reducing-dust-levels-worldwide-as-arctic-temperature-warms-study.jpg)

![Tsunami Hazard Zones: New US Map Shows Places at Risk of Flooding and Tsunamis Amid Rising Sea Levels [NOAA]](https://1471793142.rsc.cdn77.org/data/thumbs/full/70325/280/157/50/40/tsunami-hazard-zones-new-us-map-shows-places-at-risk-of-flooding-and-tsunamis-amid-rising-sea-levels-noaa.jpg)