Florida state wildlife officials and specialists spent this week searching for northern African rock pythons just outside of the Everglades in a continued effort to keep the species from invading the vulnerable tropical wetlands. They called it quits on Thursday, reporting zero finds, and while that may sound bad, it's actually really good news.

Since their discovery in 2001 in Miami-Dade County, 29 of these large invasive constrictors have been hunted down and captured during monthly surveys. The snake hunts are all part of an effort launched by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) to keep the python from reaching its other invasive cousins, the infamous Burmese python, which has been wreaking havoc in the Everglades for far too long.

"Unlike the Burmese python in Florida, the Northern African python population is thought to be confined to a small area in a single county," FWC biologist Jenny Ketterlin Eckles explained in a statement. "Focused efforts by the FWC and partners to locate and remove these invasive snakes could prevent the spread of this species into natural areas and inform management actions to address the Burmese python population."

And Eckles remains hopeful. Turning up empty-handed after a week-long hunt for the snakes along the rugged Tamiami Trail is actually a very good thing. According to the FWC, their staff and the specialists it commissions have had years to hone their snake-hunting skills in search for the massive (up to 20 feet long), but often well-concealed predators. If they can't find them, it's very likely that few are left.

"We think they're confined to a small area," Eckles reiterated in an interview with the Sun Sentinel. "We are increasing our efforts in hopes that we can eradicate them."

She added that no one exactly knows how the snakes got there in the first place, but like with the Burmese, all it takes is a pair of escapees from a careless pet owner's home to birth a powerful invading force.

And in the case of the Burmese python army, conservationists and wildlife officials were made aware of it far too late. Last year alone 141 Burmese were removed from the 1.5 million-acre Everglades National Park, and ecologists say it's very likely that that barely dented the snakes' population. There, it's even harder to find pythons than it is in Florida suburbs and the Tamiami Trail, even while the snakes are surrounded by prey with hardly any predators strong enough to threaten them. In these conditions, they can breed like crazy and disrupt a delicate ecosystem in the process. (Scroll to read on...)

That's one of the leading reasons that the FWC can't afford to let the northern African rock python reach the wetlands as well. It's one thing to fight a costly war of attrition against one snake army, but two? That would be a catastrophe.

Still, with this last hunt ending in zero discoveries, victory may be close at hand. Eckles added that while she doesn't believe the fight against the African python is done yet, the FWC will likely be able to declare their work a success if the snake doesn't resurface over the next few years.

"It's a big deal to have a success story and say we did it," Brian Smith, a University of Florida researcher, told the Miami Herald.

The problem, he went on to say, is that resolving the African python problem will do nothing to help solve the Burmese conundrum. The difference in hunting methods and situation, he explained, is too great.

Frank Mazzotti, a colleague of Smith's and a wildlife ecologist, added that currently biologists only have only a one percent detection rate for Burmese in the Everglades. That rate, he suggests, needs to be at least 50 times greater to make an impact.

"We're not going to win this war until we develop the atom bomb," Mazzotti told the Herald.

The trouble is, despite a tentative victory on a nearby front, that hypothetical war-winning bomb remains a pipe dream.

For more great nature science stories and general news, please visit our sister site, Headlines and Global News (HNGN).

© 2024 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

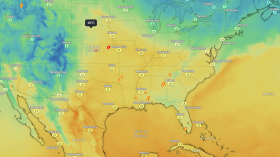

![Severe Weather Threat to Impact Over 40 Million Americans Across Central US [NOAA]](https://1471793142.rsc.cdn77.org/data/thumbs/full/70189/280/157/50/40/severe-weather-threat-to-impact-over-40-million-americans-across-central-us-noaa.jpg)